It’s wrong to expect a “snap-back” at shopping centres, food courts, cinemas and other places where people used to gather to spend money.

We’ve identified three reasons why spending in physical stores on goods like clothes is likely to remain much lower than it was for a long time.

1. Fear, much of it age-based

First, even when governments relax restrictions, lots of people will still be worried and will go out less. Unless there are zero cases for several weeks in a state or city, many people will remain reluctant to go out.

This is why we have previously argued that there is a big dividend in eliminating COVID-19 in the style of New Zealand, the Northern Territory, and South Australia, rather than bumping along with “suppression” – and several new locally-acquired cases a day – as Victoria is still doing.

This reluctance to go out and spend, irrespective of government restrictions, could be seen in Australia before government restrictions were imposed, as shown on the “Consumers and mobility” tab of the Grattan Econ Tracker.

The effects of fear shouldn’t be underestimated.

Spending in Sweden has fallen almost as much as in Denmark, even when Denmark was in lockdown and Sweden had minimal restrictions. Swedes are afraid to go out, particularly if they are old.

Spending by people aged 70+ has fallen further in Sweden than in Denmark, and 60-69 year-olds have cut their spending by about the same amount in both countries.

This isn’t surprising. COVID-19 is much more deadly for older people.

Age-based fear is a challenge for retailers because older households now spend significantly more than younger households. 25 years ago it was the other way around.

2. Time to form new habits

Second, we are likely to keep spending on different things, and using different channels, even after restrictions are lifted.

Habits tend to form when behaviour changes consistently. They strengthen over time, and are particularly sticky once behaviour has been consistent for a period of months – and we’ve been living with lockdown for that long in Australia.

Once formed, the new habits can persist unless there is another shock.

Australians have become used to doing more of their purchasing online. They have become used to spending more on living comfortably at home, and less on clothes for the office and to go out.

After the shutdown, people are likely to continue to work from home more often.

The habits of shopping remotely, and spending more on home furnishings and less on clothes, are likely to continue, and they would be likely to continue even if COVID-19 vanished tomorrow.

3. Global recession

Third, irrespective of COVID-19 regulations and behaviours, we are heading into an “old-fashioned”, globally synchronised, deep recession.

For the moment, JobKeeper, the temporarily-boosted JobSeeker payment, and a recent bounceback, have resulted in spending on credit and debit cards a bit more than this time last year.

But unemployment jumped to 7.1% on Thursday. That official rate understates how bad things are.

In May an extra 227,700 Australians lost their jobs (on top of 607,400 in April).

But only 85,000 of them were counted as unemployed. When and if the bulk of those people look for work, the unemployment rate will climb further.

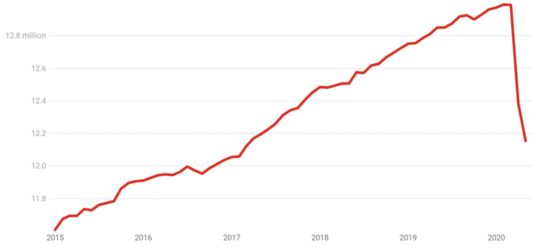

Employed Australians, total

Includes Australians regarded as still employed because they are on JobKeeper. ABS 6202.0

Includes Australians regarded as still employed because they are on JobKeeper. ABS 6202.0

After JobKeeper ends in September (or is phased out as a result of the government’s review) many of the three million people on it will also become counted as unemployed.

Australians who have lost their jobs are likely to spend less than they did before.

After each of the previous two recessions it took years for employment to recover.

Spending need not recover after COVID

These three factors – fear, new habits, and recession – are present in countries and regions that seem to be well clear of coronavirus.

Much of China has been free of most government restrictions for months. Manufacturing and infrastructure spending has largely returned to pre-COVID levels.

But consumer activity is still below pre-COVID levels, and it is inching up only slowly.

Australia might well see an “opening party” on the day each particular COVID-19 restriction is lifted.

But after that, the best guess is that consumer spending will remain very subdued and refocused for a long time.

For those in the hardest-hit sectors and regions – particularly arts and recreation, hospitality, and clothing – the pain will continue long after the restrictions are lifted.![]()

About The Author

John Daley, Chief Executive Officer, Grattan Institute

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Recommended books:

Capital in the Twenty-First Century

by Thomas Piketty. (Translated by Arthur Goldhammer)

In Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Thomas Piketty analyzes a unique collection of data from twenty countries, ranging as far back as the eighteenth century, to uncover key economic and social patterns. But economic trends are not acts of God. Political action has curbed dangerous inequalities in the past, says Thomas Piketty, and may do so again. A work of extraordinary ambition, originality, and rigor, Capital in the Twenty-First Century reorients our understanding of economic history and confronts us with sobering lessons for today. His findings will transform debate and set the agenda for the next generation of thought about wealth and inequality.

In Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Thomas Piketty analyzes a unique collection of data from twenty countries, ranging as far back as the eighteenth century, to uncover key economic and social patterns. But economic trends are not acts of God. Political action has curbed dangerous inequalities in the past, says Thomas Piketty, and may do so again. A work of extraordinary ambition, originality, and rigor, Capital in the Twenty-First Century reorients our understanding of economic history and confronts us with sobering lessons for today. His findings will transform debate and set the agenda for the next generation of thought about wealth and inequality.

Click here for more info and/or to order this book on Amazon.

Nature's Fortune: How Business and Society Thrive by Investing in Nature

by Mark R. Tercek and Jonathan S. Adams.

What is nature worth? The answer to this question—which traditionally has been framed in environmental terms—is revolutionizing the way we do business. In Nature’s Fortune, Mark Tercek, CEO of The Nature Conservancy and former investment banker, and science writer Jonathan Adams argue that nature is not only the foundation of human well-being, but also the smartest commercial investment any business or government can make. The forests, floodplains, and oyster reefs often seen simply as raw materials or as obstacles to be cleared in the name of progress are, in fact as important to our future prosperity as technology or law or business innovation. Nature’s Fortune offers an essential guide to the world’s economic—and environmental—well-being.

What is nature worth? The answer to this question—which traditionally has been framed in environmental terms—is revolutionizing the way we do business. In Nature’s Fortune, Mark Tercek, CEO of The Nature Conservancy and former investment banker, and science writer Jonathan Adams argue that nature is not only the foundation of human well-being, but also the smartest commercial investment any business or government can make. The forests, floodplains, and oyster reefs often seen simply as raw materials or as obstacles to be cleared in the name of progress are, in fact as important to our future prosperity as technology or law or business innovation. Nature’s Fortune offers an essential guide to the world’s economic—and environmental—well-being.

Click here for more info and/or to order this book on Amazon.

Beyond Outrage: What has gone wrong with our economy and our democracy, and how to fix it -- by Robert B. Reich

In this timely book, Robert B. Reich argues that nothing good happens in Washington unless citizens are energized and organized to make sure Washington acts in the public good. The first step is to see the big picture. Beyond Outrage connects the dots, showing why the increasing share of income and wealth going to the top has hobbled jobs and growth for everyone else, undermining our democracy; caused Americans to become increasingly cynical about public life; and turned many Americans against one another. He also explains why the proposals of the “regressive right” are dead wrong and provides a clear roadmap of what must be done instead. Here’s a plan for action for everyone who cares about the future of America.

In this timely book, Robert B. Reich argues that nothing good happens in Washington unless citizens are energized and organized to make sure Washington acts in the public good. The first step is to see the big picture. Beyond Outrage connects the dots, showing why the increasing share of income and wealth going to the top has hobbled jobs and growth for everyone else, undermining our democracy; caused Americans to become increasingly cynical about public life; and turned many Americans against one another. He also explains why the proposals of the “regressive right” are dead wrong and provides a clear roadmap of what must be done instead. Here’s a plan for action for everyone who cares about the future of America.

Click here for more info or to order this book on Amazon.

This Changes Everything: Occupy Wall Street and the 99% Movement

by Sarah van Gelder and staff of YES! Magazine.

This Changes Everything shows how the Occupy movement is shifting the way people view themselves and the world, the kind of society they believe is possible, and their own involvement in creating a society that works for the 99% rather than just the 1%. Attempts to pigeonhole this decentralized, fast-evolving movement have led to confusion and misperception. In this volume, the editors of YES! Magazine bring together voices from inside and outside the protests to convey the issues, possibilities, and personalities associated with the Occupy Wall Street movement. This book features contributions from Naomi Klein, David Korten, Rebecca Solnit, Ralph Nader, and others, as well as Occupy activists who were there from the beginning.

This Changes Everything shows how the Occupy movement is shifting the way people view themselves and the world, the kind of society they believe is possible, and their own involvement in creating a society that works for the 99% rather than just the 1%. Attempts to pigeonhole this decentralized, fast-evolving movement have led to confusion and misperception. In this volume, the editors of YES! Magazine bring together voices from inside and outside the protests to convey the issues, possibilities, and personalities associated with the Occupy Wall Street movement. This book features contributions from Naomi Klein, David Korten, Rebecca Solnit, Ralph Nader, and others, as well as Occupy activists who were there from the beginning.

Click here for more info and/or to order this book on Amazon.