A Los Angeles County police graduation ceremony, Aug. 21, 2020 in Monterey Park, Calif. Mario Tama/Getty Images

A Los Angeles County police graduation ceremony, Aug. 21, 2020 in Monterey Park, Calif. Mario Tama/Getty Images

Police academies provide little training in the kinds of skills necessary to meet officers’ growing public service role, according to my research.

Highly publicized cases of police violence – such as the 2020 murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis and 2014 shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri – often raise questions about police training, and whether officers are prepared to do the job that is expected of them.

As a public administration researcher who conducts leadership training for law enforcement supervisors across the country, I set out to investigate what future police officers learn in basic training – specifically, whether they are taught the kind of public service skills that many people expect them to display on the job.

How police are trained

Police officers, like their counterparts in other government agencies, are public servants. Unlike most public servants, however, officers have the legal power to deprive citizens of their freedom in a split-second decision, at their own discretion, possibly while pointing a gun.

Given their extraordinary powers, it would be reasonable to expect that officers are thoroughly trained on the values of public service – especially, how to make ethical and unbiased decisions when dealing with civilians.

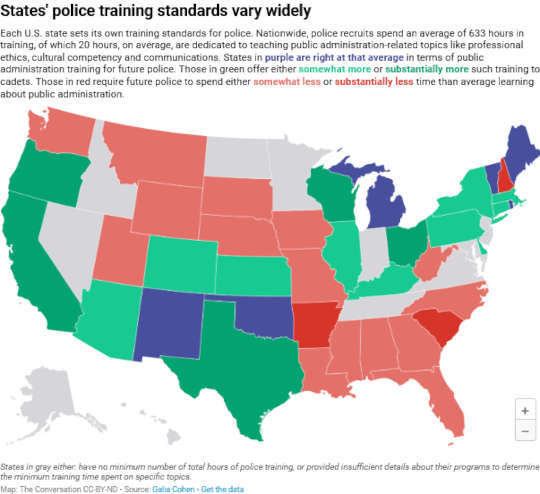

My recent study compared state-mandated basic police training curricula across the 50 U.S. states. I found that police recruits in the U.S. spend an average of 633 hours completing the basic academy, a training program that certifies them as licensed police officers.

Of those 633 hours, only 20 hours are dedicated to what is defined in my study as “public administration training” – knowledge and skills that are not law enforcement-specific but rather relevant to all public service professions such as city administrators, educators and social workers. That means 3.21% of the basic academy curricula is dedicated to public administration training.

Specifically, I found that the average police recruit in the U.S. receives 5.5 hours of ethics and boundaries training, 7.3 hours of human relations and interpersonal communications training, 6.1 hours of cultural competency training, 5.6 hours of procedural justice training and another 4.3 hours of training on other public service core values, such as effective problem solving and the use of discretionary powers.

The sample size for each topic area was different, as each state’s police training differs.

The remaining 613 hours, on average, focus on tasks and knowledge relevant only to the profession of law enforcement. These topics include, but are not limited to, report writing, driving skills, patrol procedures, defensive tactics, criminal and constitutional law, traffic stops and firearms training.

That means that most U.S. police cadets spend about 20 hours of their entire basic training learning the kind of knowledge and skills that are considered foundational for all other public service professions.

States train police differently

States varied widely in both the length of basic police training and the public service content of their training curricula.

Georgia ranks the lowest nationwide in compulsory minimum training hours for police recruits, with only 408 hours compared to the national average of 633 hours. Only 10 of those 408 hours of training are dedicated to public administration, and just one hour of that focuses on ethics.

Rhode Island requires the highest minimum training for its police of any other state: 953 hours. However, the state requires below-average public administration training for future police – 2.3% of its curriculum, or 22 hours.

With 640 compulsory minimum training hours, Oregon is right at the national average for total training time but requires the most extensive public administration training for police recruits: 46.5 hours of Oregon’s curriculum, or 7.26%, are dedicated to teaching public service values, with specific emphasis on human relations and interpersonal communications.

Hawaii is the only U.S. state that does not have any legally required minimum standards for basic police training.

Prepared for battle, not building trust

The data reported in my study shed new light on the misalignment between how police officers are trained to work and what the American public expects of them on the job.

The role of the modern-day police officer has changed. Research on community expectations of police show that the U.S. public expects officers to be honest, respectful – and even to provide emotional comfort when needed.

In other words, the public expects police officers to demonstrate principles of “procedural justice” – a big concept in policing that basically means citizens should have a voice when interacting with police, that officers are transparent and resolve conflicts in a fair and impartial way.

One police training official I interviewed said “most rookies fresh out of the academy” have “no idea” what procedural justice is. They think procedural justice is “about white cops [not] shooting black people.” It is not, he said – it is about “building partnerships with the community [and] about trust.”

Yet police academies still use the traditional, para-military training model that trains officers to be soldiers ready for combat with “the enemy” – not culturally competent public servants ready to engage civilians in difficult dialogues.

Even officers themselves know this is a problem. When I conduct police training, police supervisors often tell me that the first thing they say to a rookie on their first day on the job is “forget everything you learned in the academy, this is real police now.”

These seasoned cops know that the training recruits get in the academy is largely irrelevant to the reality of day-to-day police work. As my study shows, police recruits leave the academy armed with plenty of tactical skills but relatively few communications and cultural competency skills – the skills, veterans of the force know, officers most need to use throughout their day.

Some people in the U.S. may not be happy with the police they have – but they are getting the police they train.

About The Author

Galia Cohen, Assistant Professor, Director of the Division of Public Administration, Tarleton State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.