But where this plastic ends up and what form it takes is a mystery. Most of our waste consists of everyday items such as bottles, wrappers, straws or bags. Yet the vast majority of debris found floating far offshore is much smaller: it’s broken-down fragments smaller than your pinky fingernail, termed microplastic.

In a newly published study, we showed that this floating microplastic accounts for only about 1% of the plastic waste entering the ocean from land in a single year. To get this number – estimated to be between 93,000 and 236,000 metric tons – we used all available measurements of floating microplastic together with three different numerical ocean circulation models.

Getting A Bead On Microplastics

Our new estimate of floating microplastic is up to 37 times higher than previous estimates. That’s equivalent to the mass of more than 1,300 blue whales.

The increased estimate is due in part to the larger data set – we assembled more than 11,000 measurements of microplastics collected in plankton nets since the 1970s. In addition, the data were standardized to account for differences in sampling conditions.

For example, it has been shown that trawls carried out during strong winds tend to capture fewer floating microplastics than during calm conditions. That’s because winds blowing on the sea surface create turbulence that pushes plastics down to tens of meters depth, out of reach of surface-trawling nets. Our statistical model takes such differences into account.

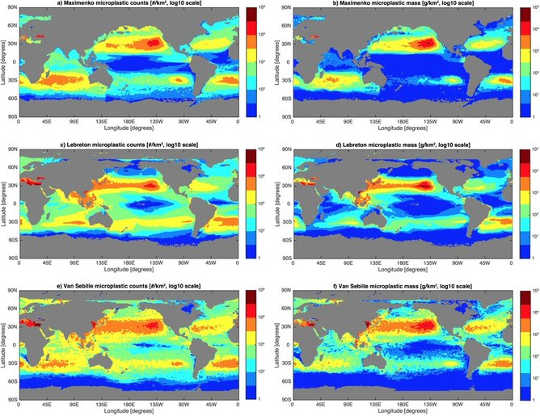

Maps of three model solutions for the amount of microplastics floating in the global ocean as particle counts (left column) and as mass (right column). Red colors indicate the highest concentrations, while blue colors are the lowest. van Sebille et al (2015)The broad range in our estimates (93 to 236 thousand metric tons) stems from the fact that vast regions of the ocean have not yet been sampled for plastic debris.

Maps of three model solutions for the amount of microplastics floating in the global ocean as particle counts (left column) and as mass (right column). Red colors indicate the highest concentrations, while blue colors are the lowest. van Sebille et al (2015)The broad range in our estimates (93 to 236 thousand metric tons) stems from the fact that vast regions of the ocean have not yet been sampled for plastic debris.

It is widely understood that the largest concentrations of floating microplastics occur in subtropical ocean currents, or gyres, where surface currents converge in a kind of oceanographic “dead-end.”

These so-called “garbage patches” of microplastics have been well-documented with data in the North Atlantic and North Pacific oceans. Our analysis includes additional data in less sampled regions, providing the most comprehensive survey of the amount of microplastic debris to date.

However, very few surveys have ever been carried out in the Southern Hemisphere oceans and outside of the subtropical gyres. Small differences in the oceanographic models give vastly different estimates of microplastic abundance in these regions. Our work highlights where additional ocean surveys must be done in order to improve microplastics assessments.

And The Rest?

Floating microplastics collected in plankton nets are the best-quantified type of plastic debris in the ocean, in part because they were initially noted by researchers collecting and studying plankton decades ago. Yet microplastics represent just part of the total amount of plastic now in the ocean.

After all, “plastics” is a collective term for a variety of synthetic polymers with variable material properties, including density. This means some common consumer plastics, such as PET (resin code #1, stamped on the bottom of clear plastic drink bottles, for example), are denser than seawater and will sink upon entering the ocean. However, measuring plastics on the seafloor is very challenging in shallow waters close to shore, let alone across vast ocean basins with an average depth of 3.5 kilometers.

It’s also unknown how much of the eight million metric tons of plastic waste entering the marine environment each year lies on beaches as discarded items or broken-down microplastics.

In a one-day cleanup of beaches around the world in 2014, International Coastal Cleanup volunteers collected more than 5,500 metric tons of trash, including more than two million cigarette butts and hundreds of thousands of food wrappers, drink bottles, bottle caps, drinking straws and plastic bags.

We do know that these larger pieces of plastics will eventually become microparticles. Still, the time it takes large objects – including consumer products, buoys and fishing gear, for example – to fragment to millimeter-sized pieces upon exposure to sunlight is essentially unknown.

Just how small those pieces become before (or if) they are degraded by marine microorganisms is even less certain, in large part because of the difficulty in collecting and identifying microscopic particles as plastics. Laboratory and field experiments exposing different plastics to environmental weathering will help unravel the fate of different plastics in the ocean.

Why It Matters

If we know that a massive amount of plastic is entering the ocean each year, what does it matter if it is a bottle cap on a beach, a lost lobster trap on the seafloor, or a nearly invisible particle floating thousands of miles offshore? If plastic trash were simply an aesthetic problem, perhaps it wouldn’t.

But ocean plastics pose a threat to a wide variety of marine animals, and their risk is determined by the amount of debris an animal encounters, as well as the size and shape of the debris.

To a curious seal, an intact packing band, a loop of plastic used to secure cardboard boxes for shipping, drifting in the water is a serious entanglement hazard, whereas bits of floating microplastic might be ingested by large filter-feeding whales down to nearly microscopic zooplankton. Until we know where the millions of tons of plastics reside in the ocean, we can’t fully understand the full suite of its impacts on the marine ecosystem.

Yet we don’t have to wait for more research before working on solutions to this pollution problem. For the few hundred thousand tons of microplastic floating in the ocean, we know that it is not feasible to clean up these nearly microscopic particles distributed across thousands of kilometers of the sea surface. Instead, we have to turn off the tap and prevent this waste from entering the ocean in the first place.

In the short term, effective waste collection and waste management systems must be put in place where they are needed most, in developing nations such as China, Indonesia and the Philippines where fast economic growth accompanied by increased waste is outpacing the capacity of infrastructure to manage this waste. In the longer term, we must rethink how we use plastics with respect to function and desired lifetime of products. At the end of its life, discarded plastic should be considered a resource for capture and reuse, rather than simply a disposable convenience.

About The Authors

Kara Lavender Law, Research Professor of Oceanography, Sea Education Association and Erik van Sebille, Lecturer in Oceanography and Climate Change, Imperial College London

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Related Book:

at

Thanks for visiting InnerSelf.com, where there are 20,000+ life-altering articles promoting "New Attitudes and New Possibilities." All articles are translated into 30+ languages. Subscribe to InnerSelf Magazine, published weekly, and Marie T Russell's Daily Inspiration. InnerSelf Magazine has been published since 1985.

Thanks for visiting InnerSelf.com, where there are 20,000+ life-altering articles promoting "New Attitudes and New Possibilities." All articles are translated into 30+ languages. Subscribe to InnerSelf Magazine, published weekly, and Marie T Russell's Daily Inspiration. InnerSelf Magazine has been published since 1985.