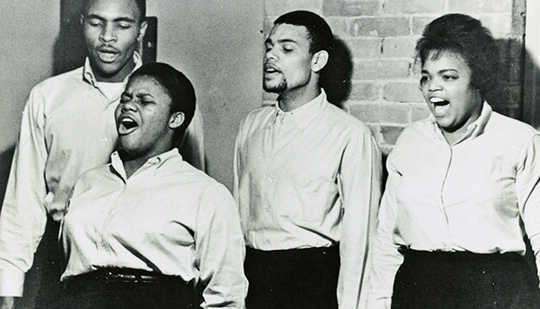

Pictured, left to right, Charles Neblett, Bernice Johnson, Cordell Reagon and Rutha Harris sing together in 1963. (Credit: Joe Alper/Library of Congress)

While “freedom songs” were key in giving motivation and comfort to those fighting for equal rights in the Civil Rights Movement, music may have also helped empower black women to lead when formal leadership positions were unavailable, according to new research.

When Nina Simone belted out “Mississippi Goddam” in 1964, she gave voice to many who were fighting for equal rights during the Civil Rights Movement. The lyrics didn’t shy away from the anger and frustration that many were feeling.

AnneMarie Mingo, assistant professor of African American studies and women’s, gender, and sexuality studies at Penn State, says women were often denied formal positions as preachers or other community leaders, and they needed to find other ways to exert public influence.

“Leading others in song gave these women space where very often they were prohibited from positions of power and leadership,” Mingo says. “But through song, they were able to give direction to the movement and sustenance to those who were fighting for equal rights. They were able to improvise and mold songs into what they wanted to say.”

Oral history

For the study, which appears in the journal Black Theology, Mingo interviewed more than 40 women who lived through and participated in the Civil Rights Movement. She recruited the women at four US churches: Ebenezer Baptist Church and Big Bethel A.M.E. Church, both in Atlanta, Georgia; and Abyssinian Baptist Church and First A.M.E. Church Bethel, both in Harlem, New York.

Mingo says it was important for the women to volunteer for the study, because oftentimes even the church pastors did not know the women had participated in the Civil Rights Movement. For example, one woman had been arrested multiple times in Atlanta with Martin Luther King Jr., which no one from her church knew.

Learning these oral histories is important, Mingo says, for finding and documenting these pieces of history that may otherwise be forgotten.

“I wanted to learn what gave women the strength to keep going out and protesting day after day and risking all the things that they risked,” Mingo says. “And one of the things was their understanding of God, and the way they articulated that understanding, or theology, wasn’t by going to seminary and writing some long treatise, but by singing and strategically adding or changing the lyrics to songs.”

Songs of the Civil Rights Movement

After hearing the women’s stories, Mingo noted the songs that came up repeatedly as having been influential during the time period. She then did further research with historical sources to verify information. For example, she used archival recordings of freedom songs sung in mass meetings and compared them to published song books to see how lyrics may have changed over time.

One of the songs that deeply resonated with study participants was “Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me ‘Round.” A spiritual that originated in the 1920s or earlier, the song’s lyrics were altered during the Civil Rights Movement to reflect the struggles of the time.

Various versions included such lyrics as “Ain’t gonna let segregation turn me ’round,” “Ain’t gonna let racism turn me ’round,” and “Ain’t gonna let Bull Connor turn me ’round,” among other renditions.

“I realized that what they were doing with music was transgressive,” Mingo says. “They were allowing it to open up new spaces for them, especially as women and as young people. They could use music as a way of articulating their own pain, their own concerns, their own questions, their own political statements and critiques. Music democratized the Movement in ways that other things could not.”

Other popular songs of the era were “We Shall Overcome,” “God Be with You Till We Meet Again,” “Walk with Me, Lord,” and “Say It Loud—I’m Black and I’m Proud.”

Mingo says the use of songs as a form of resistance is still alive and well today, with tunes that were popular during the Civil Rights Movement being repurposed and molded to fit current struggles. For example, the song “Which Side Are You On?” originated during the union movement in the 1930s, was changed and adapted during the Civil Rights Movement, and has been updated again recently with new lyrics.

Additionally, Mingo says that as the popularity of the black church with young people seems to wane, artists like Beyoncé, Janelle Monáe, and Kendrick Lamar, among others, “take on the role of the preacher and prophet by speaking truth to power from the stage or via social media.”

Contemporary songs that Mingo cites include “Alright” by Kendrick Lamar, “Be Free” by J. Cole, and “Freedom” by Beyoncé.

Mingo says she hopes her research can be an example of how theology can be revealed in the everyday lives of people as they use art to make sense of their world through God.

“Communicating through song gives broader access to these thoughts and beliefs than traditional theological or ethical texts because you have to put philosophies in accessible language in music or else it doesn’t work,” Mingo says.

“It’s about finding ways for all of us to creatively articulate what we’re feeling, longing for, hoping for, and even criticizing. That can all happen through music. It can bring people together the way other things can’t.”

Source: Penn State