The ancient understanding of the universe was as a unified whole. Parmenides described the universe as a single, unified block of being. Then Plato split apart this unity with his ontological distinction between Heaven and Earth. Descartes’s mind-body dualism further removed humanity from nature by excluding consciousness from the natural world. Following Descartes, the major unresolved philosophical and scientific mystery has hinged on explaining the relationship between the fact of consciousness and the assumed insentience of nature.

The third schism occurred after another paradigm shift: empiricism and the rise of scientific materialism threatened both Platonic and Cartesian dualism.

Today, secular materialism views humans as natural products of evolution and places our species at the top of the great chain. Human exceptionalism and opposition remains, carried into a secular modernity through social Darwinism.

Thomas Robert Malthus (1766–1834), cleric and scholar, influenced social Darwinism more than Darwin himself. The “Malthusian catastrophe,” named after him, stated that famine and disease check the growth of populations.

A Theory of Eternal Struggle

Malthus repudiated the popular utopianism of his contemporaries, predicting instead a theory of eternal struggle—ordained by God to teach virtue to humanity. In An Essay on the Principle of Population, he calculated that humanity’s drive to -procreate would eventually outstrip available resources. He opposed the Poor Laws—the original welfare system—blaming it for an increase in taxation. He believed that “moral constraint” would most effectively prevent overpopulation and resulting lack of resources.

Malthus-inspired hardline policies on poverty and population control showed up in the works of Charles Dickens, which portrayed the bleak poverty rampant in industrial Victorian England. Echoes of Malthusianism reverberate throughout our current political policies.

Meanwhile the characterization of nature as “eternal struggle and competition for resources” influenced Darwin’s theory. He acknowledged that Malthus’s inspired On the Origin of Species: “The doctrine of Malthus [applies] to the whole animal and vegetable kingdoms.”

For Malthus and Darwin, this “endless struggle” characterized the dynamics of nature—reminiscent of Empedocles’s strife and Schopenhauer’s endless striving. The struggle, strife, and competition of Origin of Species had a greater influence on subsequent biologists and sociologists than the cooperation documented in Darwin’s other great work, The Descent of Man. Indeed Darwin’s later work portrays a more cooperative story of evolution.

Huxley, a staunch advocate of Darwinism, viewed morality through the lens of secular science. He noted: “Science commits suicide when it adopts a creed,” hinting at the looming shadow of scientism. Huxley regarded humans as complicated, “unsociably sociable” animals. Inspired by Kant, Huxley believed that humans, compelled to live separate from nature in a civilized world, had to suppress our natural instincts, leaving us with ever-warring internal states. Following Descartes’s mind-matter split and Darwinian notions of evolutionary struggle for survival, Huxley saw competition as nature’s imperative.

Herbert Spencer (1820–1903), a polymath philosopher, biologist, anthropologist, and sociologist, developed social Darwinism—a theory that supported his liberal political ideas. He presented his synthetic philosophy as an alternative to Christian morality, believing that universal scientific laws will eventually explain everything. He rejected vitalism and intelligent design, as well as Goethean science and everything transcendental. Whereas Huxley elevated agnosticism to a secular faith, Spencer sought to knock the wind out of any remaining teleology.

Survival Of The Fittest?

Independently of Darwin, Spencer saw evolutionary changes as a result of environmental and social forces rather than of internal or external agents, proposing that life is the “co-ordination of actions.” In his Principles of Biology he proposed the concept of “survival of the fittest, . . . which I have here sought to express in mechanical terms, is that which Mr. Darwin has called ‘natural selection,’ or the preservation of favoured races in the struggle for life.” He famously said that life’s history has been “a ceaseless devouring of the weak by the strong.”

Spencer's political and sociological ideas, derived from his evolutionary perspective, deeply influenced postmodern America—in particular, the idea that the fittest in society will naturally rise to the top and create the most benevolent society. Assuming this evolutionary trajectory, Spencer predicted a future of benevolent harmony for humanity.

Spencer’s sociological theories ran into paradoxes. Although Spencer believed that “sympathy” inhered in human nature, he saw it as a recent evolutionary development. As in biology, he regarded struggle as central to his political ideology, which celebrated laissez-faire capitalism. He even described “cupidity,” or greed, as a virtue, exemplified in our times by the Wall Street avarice of Gordon Gecko’s “greed is good” slogan.

In 1884 Spencer argued in The Man Versus the State that social programs to aid the elderly and disabled, the education of children, or any health and welfare went against nature’s order. In his opinion, unfit individuals should be left to perish in order to strengthen the race. His was a cruel philosophy that could be used to justify the worst impulses of human beings. Unfortunately, Spencer’s sinister ideologies influence much of our current government’s worldview and policy.

Cut-throat, Competition-based Sociopolitical Ideologies

Taking its cue from Hobbesian-Malthusian views on nature, social Darwinism justified cut-throat, competition-based sociopolitical ideologies. Many of the isms that plague today’s Western consciousness began here, taking a slightly different form.

Darwin, Spencer, and many of their contemporaries classified humans into different evolutionary categories. Darwin clearly supported the view that all humans have the same simian ancestors, but that intelligence evolved differently according to sex and race. Although Darwin came from a family of abolitionists, and openly detested slavery, he saw evolution as support for the idea that different humans were better suited to different purposes.

In The Descent of Man, Darwin cited comparisons of the cranial size of men and women as an indication of men’s intellectual superiority. Spencer originally argued for gender equality in his Social Statics, but he too attributed different evolutionary characteristics to the sexes and races.

Scientific justifications for racism and sexism seeped into secular society. Christian-based racism focused on the idea of the “heathen savage” contrasted with “noble” and “civilized” Christians, assuming that God had given the Earth to European Christians. This entitlement combined with a fear of otherness to create the belief that other races or ethnicities were not human, further justifying conquest and genocide. Evolutionary racism codified those superstitions, elevating them to supposedly logical assumptions.

The Myth Of Mastery Through Dogmatic Materialism

The dangerous creed of scientism has long since poisoned Western consciousness. In The Chalice and the Blade, Riane Eisler says: “Justified by the new ‘scientific’ doctrines . . . social Darwinism . . . economic slavery of ‘inferior’ races continued.”

Not only did scientific assumptions about race and gender create a new kind of slavery but, combined with mad objectivity, they generated a new level of inhumane and hostile policies toward people of color, women, and the more-than-human world. Science “justified” not only exploitation of resources but of humans and nonhumans. Scientism and positivism found justification in social Darwinism, magnifying the myth of mastery through dogmatic materialism.

Following Darwin, Huxley and Spencer advocated a Malthusian view of life as a struggle. Huxley characterized the animal world as a “gladiator show,” and asserted “the Hobbesian war of each against all was the normal state of existence.” If nature operated on the principle of incessant struggle and competition, then the same logic should be applied to human society. Spencer’s lecture tours in the United States inspired archcapitalism, a culture of avarice benefiting the “fittest” in society.

Darwin, Huxley, and Spencer lived in a world barely awakening from the bondage of church dogma. Revolutions in Europe had empowered new leadership based on industry and ability rather than on family title and inheritance. Science promised to solve many problems through a secularized, egalitarian society.

But Victorian assumptions about race, sex, and the relationship between humans and nature emphasized progress of the “fittest,” justifying runaway capitalism and blind innovation, including a medical industry that places profit before public safety. These problems have been magnified in the United States, dominated by the ideal of rugged individualism.

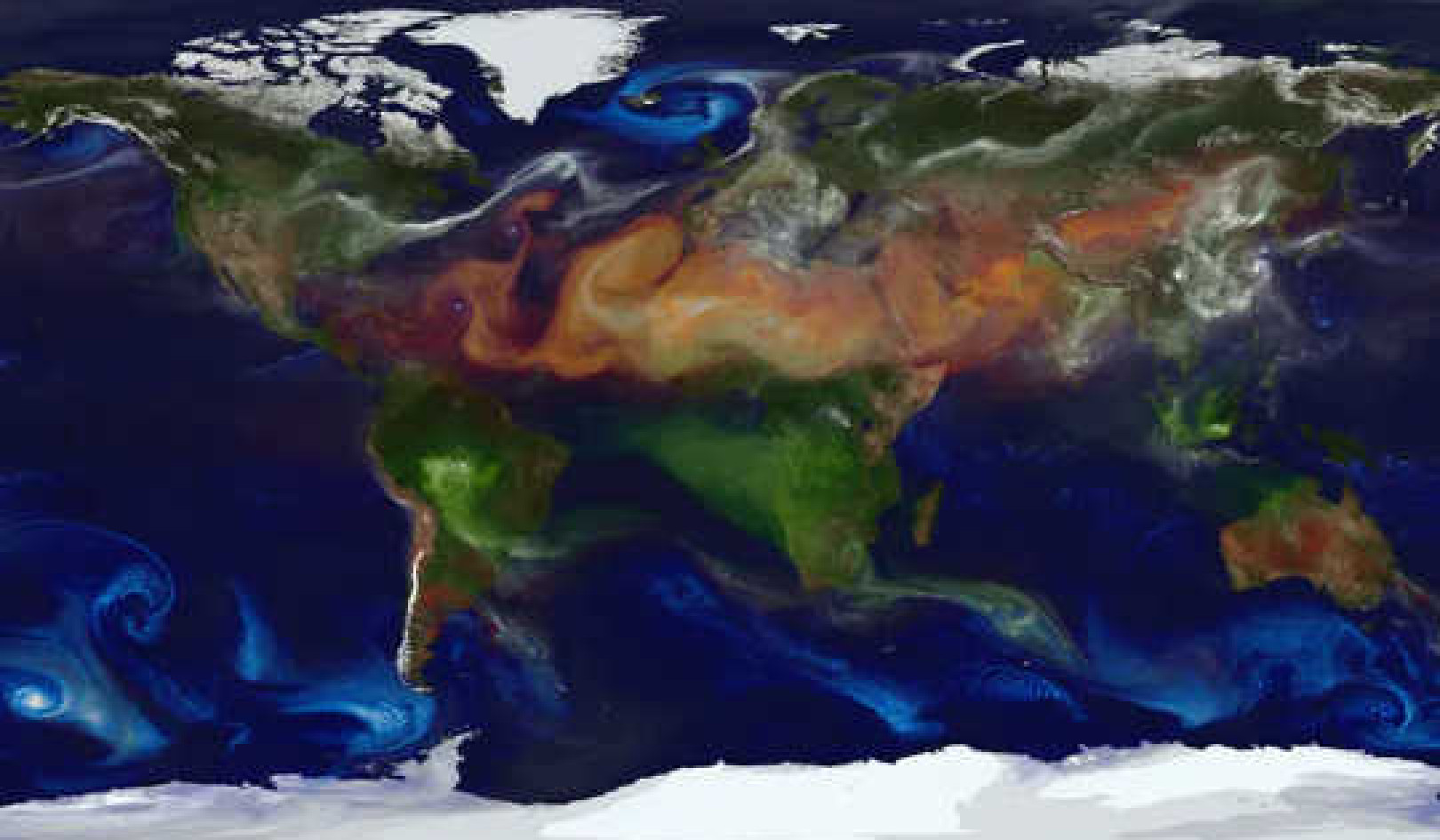

Meanwhile, the split between humans and nature, boosted by archcapitalism, has accelerated the destruction of the global ecosystem. Author Charles Eisenstein, in Ascent of Humanity, observes, “With few exceptions, modern human beings are the only living beings that think it is a good idea to completely eliminate the competition. Nature is not a merciless struggle to survive, but a vast system of checks and balances.”

Cooperation Throughout The Natural World, Including Humanity

Others reading Darwin rejected the pervasive idea of struggle and survival of the fittest. For example, Peter Kropotkin (1842–1921), a geographer, zoologist, economist, and general polymath, accused Huxley—and to a lesser degree Spencer—of incorrectly interpreting Darwin and his evolutionary theory.

In a thorough study of his own, Kropotkin pointed to the ubiquitous presence of cooperation throughout the natural world, including humanity. His great work Mutual Aid rejects the Malthusian conclusions in social Darwinism, and the assumption that natural selection results from competition within species. He describes a world of widespread interspecies and intraspecies cooperation. This alternative reading revived the idea that mutual aid, as much as or more than struggle, characterizes life.

Healing Cartesian Fragility and The Struggle Paradigm

Buddhist teacher David Loy succinctly summarized the pathology of the Cartesian paradigm: “our most problematic dualism is not life fearing death but a fragile sense-of-self dreading its own groundlessness.” He describes this fragile sense of self looking for something to fix itself to rather than surrendering to its groundlessness.

Cartesian fragility arises from lack of grounding in a relational, living, breathing, feeling web of life. Somewhere between solipsism and objectivity lies the lost self, abandoned in a primeval landscape. Whether religious or secular, Western consciousness suffers from abandonment of self and our connection to the more-than-human world.

This vital consciousness/matter inseparability brings us back to the central tenet of panpsychism. As de Quincey notes, matter “tingles with sentience” in an inseparable unity. Intentions and choices ultimately affect what happens to matter.

Indigenous people have long known that what we think affects what is, so their philosophies emphasize prayer and gratitude. Likewise, Eastern spirituality emphasizes balance between critical, deliberative thought and meditative contemplation. The quality of our thoughts creates the quality of our world.

This doesn’t mean that we can magically think ourselves into the best world. But we must radically think ourselves into a better world. As Donna Haraway puts it in Staying with the Trouble, “It matters what thoughts think thoughts.” How can we think compassionate, connected, co-creative thoughts toward possible futurity?

Healing Cartesian fragility (the lack of resilience that pervades a rigid, oppositional paradigm) and the struggle paradigm will require us to embrace a different paradigm—based on the embodied sacred and symbiosis. If nature is a complex, connected creative process in which we always participate (through feeling, thinking, and doing), then how we participate matters. How we participate ripples through reality.

Awakening from the trance of mad objectivity, the myth of mastery, and the struggle story, we might face the perils of the Anthropocene through applying nature’s connected creativity.

©2019 by Julie Morley. All Rights Reserved.

Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Park Street Press,

an imprint of Inner Traditions Inc. www.innertraditions.com

Article Source

Future Sacred: The Connected Creativity of Nature

by Julie J. Morley

In Future Sacred, Julie J. Morley offers a new perspective on the human connection to the cosmos by unveiling the connected creativity and sacred intelligence of nature. She rejects the “survival of the fittest” narrative--the idea that survival requires strife--and offers symbiosis and cooperation as nature’s path forward. She shows how an increasingly complex world demands increasingly complex consciousness. Our survival depends upon embracing “complexity consciousness,” understanding ourselves as part of nature, as well as relating to nature as sacred.

In Future Sacred, Julie J. Morley offers a new perspective on the human connection to the cosmos by unveiling the connected creativity and sacred intelligence of nature. She rejects the “survival of the fittest” narrative--the idea that survival requires strife--and offers symbiosis and cooperation as nature’s path forward. She shows how an increasingly complex world demands increasingly complex consciousness. Our survival depends upon embracing “complexity consciousness,” understanding ourselves as part of nature, as well as relating to nature as sacred.

Click here for more info and/or to order this book. Also available as a Kindle edition.

About the Author

Julie J. Morley is a writer, environmental educator, and futurist, who writes and lectures on topics such as complexity, consciousness, and ecology. She earned her B.A. in Classics at the University of Southern California and her M.A. in Transformative Leadership at the California Institute of Integral Studies, where she is completing her doctorate on interspecies intersubjectivity. Visit her website at https://www.sacredfutures.com

Julie J. Morley is a writer, environmental educator, and futurist, who writes and lectures on topics such as complexity, consciousness, and ecology. She earned her B.A. in Classics at the University of Southern California and her M.A. in Transformative Leadership at the California Institute of Integral Studies, where she is completing her doctorate on interspecies intersubjectivity. Visit her website at https://www.sacredfutures.com

Related Books

at

Thanks for visiting InnerSelf.com, where there are 20,000+ life-altering articles promoting "New Attitudes and New Possibilities." All articles are translated into 30+ languages. Subscribe to InnerSelf Magazine, published weekly, and Marie T Russell's Daily Inspiration. InnerSelf Magazine has been published since 1985.

Thanks for visiting InnerSelf.com, where there are 20,000+ life-altering articles promoting "New Attitudes and New Possibilities." All articles are translated into 30+ languages. Subscribe to InnerSelf Magazine, published weekly, and Marie T Russell's Daily Inspiration. InnerSelf Magazine has been published since 1985.