Painting building roofs white could cool some major cities baking in the intensifying heat of a changing climate. How much benefits white roofs could bring depend on the region of the country they’re installed in and the season, new research shows.

By Brian Kahn

Painting building roofs white could cool some major cities baking in the intensifying heat of a changing climate. How much benefits white roofs could bring depend on the region of the country they’re installed in and the season, new research shows.

Keeping cities cool in the summer is becoming increasingly important as more people move to urban areas, which currently house over 80 percent of the country’s population. In the U.S., cities currently cover a total of 106,386 square miles. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency expects the country’s urbanized area to double by 2100.

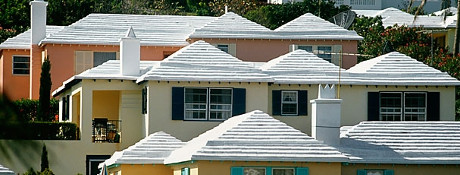

Painting white roofs in New York would cool the city but could reduce summer precipitation according to new research Credit: Community Environment Center/Flickr

Greenhouse gas emissions are expected to force average temperatures to increase between 3°F and 9°F by the end of the century, depending on how much those emissions are cut back over that period.

These increases in temperature take on added importance in cities. There, the urban heat island effect, warming caused by paved and dark surfaces, can make temperatures as much as 10°F hotter compared to greener surrounding areas. Higher summer temperatures lead to increased energy costs and a greater occurrence of heat waves, harming human health.

One method of adapting to rising urban temperatures is painting roofs white to reflect incoming sunlight. New York has mandated white roofs since 2007 and other municipalities are considering following suit.

New research published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science on Monday show that white roofs could bring benefits and drawbacks to expanding cities, though.

“We find that geography and season matters. Adaptations that work at location A might not be feasible for location B,” said Matei Georgescu, an assistant professor at Arizona State and lead author of the new study.

Georgescu and his colleagues examined six “megapolitan” areas in Arizona, California, Florida, Texas, the Mid-Atlantic, and the Midwest.

They found that urban expansion alone could increase summer temperatures by up to 3.6°F in some areas in addition to greenhouse gas-induced warming by 2100. The Mid-Atlantic and Midwest seeing the biggest overall summer temperature increases.

| RELATED | Sea Level Rise ‘Locking In’ Quickly, Cities Threatened The Easy Fix That Isn’t: White Roofs May Increase Global Warming Floods May Cost Coastal Cities $60 Billion a Year by 2050 |

|---|

Under a high emissions and urban expansion area, white roofs could offset heat island-induced temperature increases, and if deployed across the entire megapolitan area, could actually reduce some, though not all, greenhouse gas-related warming.

The benefits of cool roofs were particularly prominent for the urban areas stretching from Washington, D.C. to New York, Chicago and Detroit, and California’s Central Valley.

Cooler summertime temperatures could reduce demand for air conditioning, which could both save money and reduce the chances of electricity grid blackouts.

Keeping cities cool could also help reduce the number of heat waves and the strain they put on the public health system. According to the National Weather Service, heat is the most deadly natural hazard in the country and it can have outsized impacts on elderly city residents.

Some of the energy benefits gained in the summer could be lost in the winter, particularly in the Mid-Atlantic and Midwest.

“Once you deploy these cool roofs, they’re going to remain white into the winter season. You’re going to make your indoor environment cooler so you’ll need to use more energy to maintain your comfort,” Georgescu said.

The research indicates that winter temperatures could be 2.7°F cooler in the Mid-Atlantic if white roofs are installed across the region. However, the region would still see an overall energy savings of 9-36 percent by installing cool roofs. In comparison, energy demand would rise 39-155 percent if nothing is done to adapt.

Cecil Scheib, the chief program officer of the Urban Green Council, said that the savings would likely be greater than that. Based on research at the Lawrence Berkeley National Lab putting white roofs on current commercial buildings would provide 89 percent in net energy savings, he said.

“No one would turn down an 89% net savings, so cool roofs give a clear and compelling net benefit,” he said in an email.

However, white roofs could also have other, unintended effect on precipitation as well.

“The hotspot we found was over Florida in particular,” Georgescu said. “Over those areas . . . it needs to be warm to promote thunderstorms in late afternoon. if you reduce that heating by painting your roofs white, the effect is going to be considerable on how much rainfall you’re going to get.”

Georgescu’s research estimates that rainfall could decrease in parts of Florida by as much as 0.15 inches per day. That may not sound like much, but summer is Florida’s rainy season and thunderstorms can account for 20-40 percent of rainfall over that period.

White roofs would cause a decrease in rain from the Southwest summer monsoon, though it would be smaller. In a region that receives less overall rain, those small changes reflect a similar magnitude to projected changes in the Southeast, though it would affect water availability less since Phoenix and Tucson import most of their water from further afield.

In other locations, the impacts would less pronounced, though. Chicago and Detroit could see a slight increase in rain while in California’s Central Valley, little change would occur in part because summer is so dry.

Though it wasn’t part of the study, Georgescu said that large scale installation of cool roofs could have impacts on communities downwind.

“What you’re doing in one part location affects some things in another location. It’s difficult to say if urbanizing Florida will have an effect up the East Coast since the East Coast is also urbanizing,” he said.

Georgescu said that these tradeoffs and the interconnected nature of urban areas across the country show that, “It’s difficult to say what the ideal city (of the future) is.”

Mixing in green roofs, which have a lesser effect on summer precipitation and temperature and promote a slight winter warming, or developing seasonably adjustable cool roofs could help urban areas find a Goldilocks approach to adaptation that works just right for a specific region or city. Ultimately, climate is only one portion of making a city liveable.

“In order to really comprehensively plan the cities of tomorrow, climate folks need to start talking to planning folks and engineering folks,” Georgescu said. “What our work shows is that local solutions make a difference.”

You May Also Like

Winter Olympics Inadvertently Adapting to Climate Change

63 Years of Global Warming in 14 Seconds

Record Number of Billion-Dollar Disasters Globally in 2013

‘Atmospheric River’ May Put a Dent in California Drought

Adapting to Sea Level Rise Could Save Trillions by 2100

Follow the author on Twitter @blkahn or @ClimateCentral. We're also on Facebook & other social networks.

This article, White Roofs May Partially Offset Summer Warming by 2100, is syndicated from Climate Central and is posted here with permission. An article from NJ News Commons. This article was originally shared via the Repost Service. .

About the Author

Brian Kahn is a Web editor at Climate Central. He previously worked at the International Research Institute for Climate and Society and partnered with climate.gov to produce multimedia stories, manage social media campaigns and develop version 2.0 of climate.gov. His writing has also appeared in the Wall Street Journal, Grist, the Daily Kos, Justmeans and the Yale Forum on Climate Change in the Media. In previous lives, he led sleigh ride tours through a herd of 7,000 elk and guided tourists around the deepest lake in the U.S. He holds an M.A. in Climate and Society from Columbia University.

Brian Kahn is a Web editor at Climate Central. He previously worked at the International Research Institute for Climate and Society and partnered with climate.gov to produce multimedia stories, manage social media campaigns and develop version 2.0 of climate.gov. His writing has also appeared in the Wall Street Journal, Grist, the Daily Kos, Justmeans and the Yale Forum on Climate Change in the Media. In previous lives, he led sleigh ride tours through a herd of 7,000 elk and guided tourists around the deepest lake in the U.S. He holds an M.A. in Climate and Society from Columbia University.